Here and there, rods jut out of the ground at odd angles they protrude from tree trunks and lean against ruined stumps. But five years later, even though the old fence has been dismantled, pieces of it remain. Among the clergy and residents who gathered there that day, there was singing and prayers and promises of change. Seven months after Byrd was murdered, in one of Jasper’s many acts of contrition, the fence that had stood in the town cemetery since 1836 was torn down. “East Texas,” they offer, and if pressed further, “Near the Louisiana state line.” More than one resident made a point of telling me, with equal parts self-defensiveness and civic pride, “Jasper isn’t the evil town everyone thinks we are.” When they travel beyond the Piney Woods, they know better than to tell strangers where they live. They have worked hard to show that they renounce the ugly legacy of what happened here. Over the past five years, its residents-both black and white-have attended prayer vigils and town meetings and church services together, and they have had candid conversations with one another about race. “The incident,” or “the tragedy,” as locals gingerly call Byrd’s murder, forced this town to undertake the sort of painful introspection that few communities ever experience.

to a pickup truck in 1998 and dragged him to his death in the woods outside town did people start to wonder aloud why there was an immutable order to things in Jasper why blacks were laid to rest only on one side of the fence, on the slope of a hilltop reserved for whites. Not until three white men chained James Byrd Jr. In one place, its wobbly posts were held together with a coat hanger-anything to keep the fence from falling down. Coils of baling wire held up its rusted bars and prevented its sagging rail from giving way.

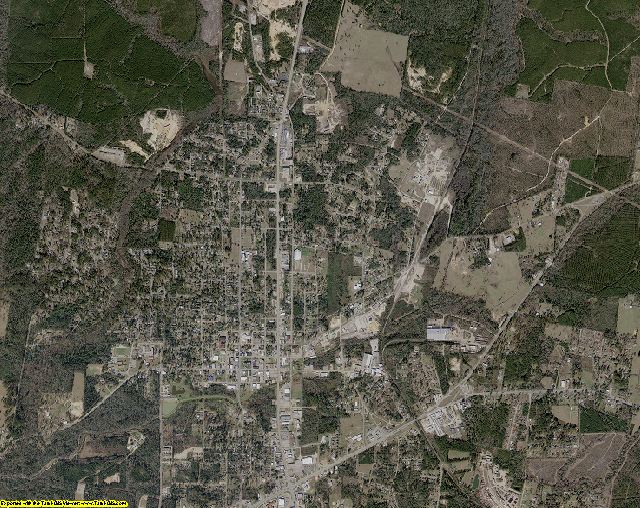

Chickens and hogs hadn’t had the run of Jasper for a long time, and still the fence remained. “It’s common knowledge that it wasn’t put there to keep out black people.” But where whites saw a benign relic, blacks saw something else. “It was just a rickety old fence that was supposed to keep out chickens and hogs when this was open land,” said realtor John Matthews, whose grandfather was the mayor of Jasper in the twenties. How residents viewed the fence depended on which side of it they would someday be buried on. BEFORE JASPER BECAME A SYMBOL, when it was still an ordinary town, a wrought-iron fence stood in its cemetery, dividing the graves of blacks and whites.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)